he 1973 Thai People's Uprising: The "October 14 Incident" and Its Legacy

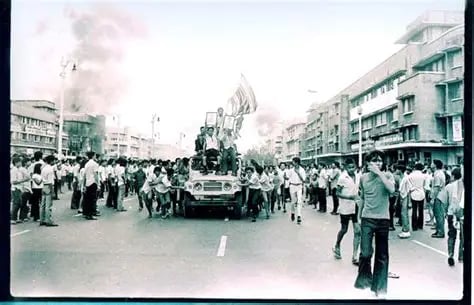

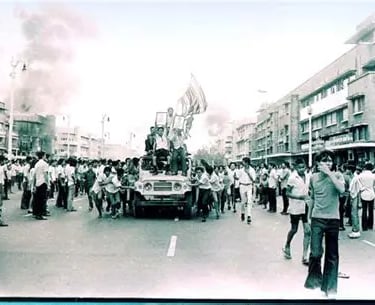

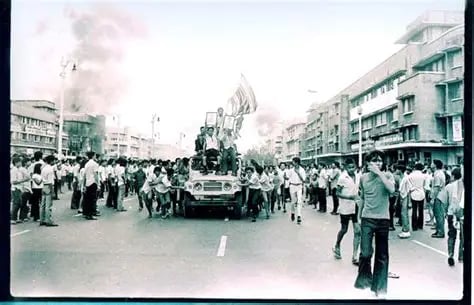

On October 14, 1973, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators—primarily university students—clashed with police and military forces at Bangkok’s Democracy Monument, leading to a bloody crackdown that forced Prime Minister Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn and his inner circle to resign and flee into exile. Known as the "October 14 Incident" (Hetkan 14 Tula) or "Day of Mourning" (Wan Maha Wippayok), this event is widely regarded as a turning point in post-war Thai political history: it briefly ended the military oligarchy’s grip on power (which had lasted since the 1950s) and ushered in a three-year period of relative liberalization (1973–1976). Importantly, the movement was not merely a "student uprising" but a broad social coalition involving workers, urban middle classes, and intellectuals. While its surface demands focused on "restoring constitutional rule" and "anti-dictatorship," the protests touched on deeper structural issues: the contradictions of national development models, urban-rural inequality, and the erosion of state autonomy under Cold War geopolitical pressures.

1/14/20266 min read

I. Introduction: The "October 14 Incident" as a Historical Watershed

On October 14, 1973, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators—primarily university students—clashed with police and military forces at Bangkok’s Democracy Monument, leading to a bloody crackdown that forced Prime Minister Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn and his inner circle to resign and flee into exile. Known as the "October 14 Incident" (Hetkan 14 Tula) or "Day of Mourning" (Wan Maha Wippayok), this event is widely regarded as a turning point in post-war Thai political history: it briefly ended the military oligarchy’s grip on power (which had lasted since the 1950s) and ushered in a three-year period of relative liberalization (1973–1976).

Importantly, the movement was not merely a "student uprising" but a broad social coalition involving workers, urban middle classes, and intellectuals. While its surface demands focused on "restoring constitutional rule" and "anti-dictatorship," the protests touched on deeper structural issues: the contradictions of national development models, urban-rural inequality, and the erosion of state autonomy under Cold War geopolitical pressures.

II. Historical Background: Accumulated Social Contradictions Under Military Rule

The foundation for the 1973 uprising was laid by decades of military authoritarianism. The 1957 coup that ousted Prime Minister Phibun Songkhram paved the way for Sarit Thanarat and Thanom Kittikachorn’s military regime, which consolidated power through the abolition of the constitution, dissolution of parliament, and bans on political parties. Sarit’s regime (1958–1963) justified its rule through anti-communism and economic modernization, relying heavily on U.S. aid and Vietnam War-related spending to fuel growth.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, Thailand’s economy had grown rapidly, but industrialization was skewed toward urban areas, and wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few conglomerates. This widened the gap between urban and rural areas, exacerbating poverty, landlessness, and corruption. Meanwhile, resentment toward U.S. military bases (which were seen as a source of social disruption) and the regime’s repression of political dissent created a tinderbox of discontent. The military’s use of martial law and censorship suppressed formal political participation, pushing opposition into universities and intellectual circles, where radical ideas began to take root.

III. Rise of Student Organizations and Political Mobilization

The National Student Center of Thailand (NSCT), founded in 1968, emerged as the core organizational platform for the 1973 movement. Initially focused on student affairs and community service, the NSCT did not directly challenge the military regime until the early 1970s. However, rising inflation, the expansion of Japanese and U.S. corporations (which fueled economic nationalism), and the regime’s crackdown on dissent pushed the NSCT toward more radical politics.

In 1972, the NSCT launched a successful boycott of Japanese goods, demonstrating its ability to mobilize support beyond campus. This success emboldened student leaders, who began to engage with socialist, anti-imperialist, and democratic theories. While the Thai Communist Party (TCP) did not formally ally with the NSCT, its discourse—including critiques of feudalism, imperialism, and dictatorship—influenced many students, spreading ideas of "democracy," "social justice," and "anti-imperialism" across campuses.

The trigger for the 1973 uprising was the June 1973 expulsion of nine Ramkhamhaeng University students for criticizing Thanom and Deputy Prime Minister Praphas Charusathien’s extension of military service. The NSCT organized a sit-in at the Democracy Monument, demanding the restoration of the constitution and an end to military rule. This marked a shift from campus-focused activism to direct confrontation with the regime.

IV. Outbreak of the Movement: From Petition to Street Confrontation

In early October 1973, 13 scholars and students were arrested for distributing leaflets demanding a new constitution, sparking days of protests. Demonstrators called for the release of the detainees and urged the government to commit to a timeline for constitutional reform. The military regime viewed this as a direct challenge to its authority.

On October 13, tens of thousands of protesters marched from Thammasat University to the Democracy Monument, surrounding Bangkok’s political center. The following day (October 14), security forces opened fire on crowds near government buildings and major intersections, using tanks and helicopters to suppress the protests. Dozens to over seventy people were killed, and hundreds to thousands injured (casualty figures vary by source).

The bloody crackdown further inflamed public anger, leading to clashes between protesters and troops across the city. The situation teetered on the brink of full-scale violence, forcing the monarchy to intervene.

V. Role of the Monarchy and Military: Limited Support and Compromise

King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) and the royal family played a pivotal role in resolving the crisis. In the official narrative, the King intervened to stop the bloodshed, compelling Thanom and Praphas to resign and go into exile. He then appointed Supreme Court Chief Justice Sanya Dharmasakti to lead a civilian interim government, which promised to draft a new constitution and hold elections.

This arrangement satisfied the protesters’ core demand—ending direct military rule—while preserving the military’s structural influence in politics. It also avoided a revolutionary collapse of the regime, maintaining stability. From a political sociology perspective, the monarchy’s mediation reflected the delicate balance of power in Thailand’s political system: the King, by "siding with the people" at a critical moment, restored some of the moral authority eroded by the military’s autocracy and channeled the movement’s radical potential into a manageable constitutional framework.

However, the 1976 Thammasat University massacre (where right-wing forces killed dozens of student protesters) revealed the limits of this compromise: the military’s structural dominance remained intact, and no stable democratic system was established.

VI. Relationship with the Left and Thai Communist Party: Alignment and Tension

The 1973 student movement is often linked to the Thai Communist Party (TCP). On one hand, scholars note that the TCP’s discourse—including anti-imperialism, anti-military dictatorship, and land reform—had a demonstration effect on student politicization since the 1960s. Many radical students were exposed to the experiences of China, Vietnam, and Cuba, which shaped their views on revolution.

On the other hand, the NSCT and other movement organizations deliberately avoided being labeled "pro-communist" to attract support from the urban middle class and moderate opposition. Their public demands focused on "democracy," "constitutional rule," and "anti-corruption," steering clear of explicit leftist slogans.

This "left-leaning values, strategic distance" approach had complex consequences. In the short term, it gave the movement broad social legitimacy. However, when the military and right-wing forces cracked down on Thammasat students in 1976 (using "anti-communism" as a pretext), many students had no choice but to join the TCP’s armed wing. This post-hoc alignment was then used by right-wing narratives to frame the 1973 movement as a "communist conspiracy."

VII. Conclusion: Democratic Myth and Capital Resurgence

The 1973 student movement succeeded in breaking the military’s "untouchable" myth and opening a crack in the edifice of Cold War authoritarianism. However, this crack was quickly sealed by the discourse of "universal democratic values," which reframed the movement’s radical potential into a form compatible with capitalism.

While the movement toppled Thanom’s regime, it also provided the system with an opportunity to renew itself: the military retreated to the background, and a civilian government (elected through "democratic" means) restored legitimacy. This allowed the urban middle class to feel that Thailand was "modernizing" and "normalizing," while reassuring Western powers that Thailand was on an "acceptable democratic path"—ensuring continued capital inflows and aid.

The 1974 constitution enshrined provisions on human rights, press freedom, and political parties, leading to a brief opening of media and public space. However, this was more of a "system detox" than genuine reform: it added a layer of "freedom and rights" to the existing order without touching the structures of conglomerates, land relations, or transnational capital. The proliferation of new political parties and civil society organizations expanded formal channels for participation but domesticated radical class politics and anti-imperialist critiques into a "manageable civil society" spectacle.

The movement expanded the boundaries of the political community, bringing the demands of workers, farmers, and urban poor into the public agenda. Issues like wealth inequality and regional disparity were discussed, but framed in technocratic terms ("uneven development," "good governance") rather than as structural exploitation or dependent capitalism. The urban, university-centric nature of the movement meant that rural and marginal areas were treated as background rather than political subjects.

Ideologically, the movement remained stuck between liberalism and moderate leftism: it borrowed the universal language of "democracy" and "human rights" but failed to develop a systematic critique of the "state-capital-military-monarchy" power bloc. When the military and conservative alliance returned to power, the movement could only appeal to procedure and morality, lacking aalternative vision to mobilize the masses.

The monarchy’s role as "final arbiter" in the crisis seemed to side with the people, but it effectively positioned itself as a moral center above politics. By ousting the military regime, it restored its symbolic authority (eroded by decades of military rule) but locked all radical possibilities into a framework of "monarchy-military-middle class" order. This left the door open for the military to use "defend the nation and the King" as a pretext for future interventions, providing endless legitimacy ammunition.

References

1. Benedict Anderson (班纳迪克·安德森): Withdrawal Symptoms: Social and Cultural Aspects of the October 6 Coup (1977).

2. Duncan McCargo: Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crisis in Thailand (2005).

3. Pasuk Phongpaichit & Chris Baker: A History of Thailand (2005) 及 Thailand's Boom and Bust.

4. Seksan Prasertkul (色讪·巴色军): The Transformation of Thai Society and Politics.

I. Introduction: The "October 14 Incident" as a Historical Watershed

On October 14, 1973, hundreds of thousands of demonstrators—primarily university students—clashed with police and military forces at Bangkok’s Democracy Monument, leading to a bloody crackdown that forced Prime Minister Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn and his inner circle to resign and flee into exile. Known as the "October 14 Incident" (Hetkan 14 Tula) or "Day of Mourning" (Wan Maha Wippayok), this event is widely regarded as a turning point in post-war Thai political history: it briefly ended the military oligarchy’s grip on power (which had lasted since the 1950s) and ushered in a three-year period of relative liberalization (1973–1976).

Importantly, the movement was not merely a "student uprising" but a broad social coalition involving workers, urban middle classes, and intellectuals. While its surface demands focused on "restoring constitutional rule" and "anti-dictatorship," the protests touched on deeper structural issues: the contradictions of national development models, urban-rural inequality, and the erosion of state autonomy under Cold War geopolitical pressures.

II. Historical Background: Accumulated Social Contradictions Under Military Rule

The foundation for the 1973 uprising was laid by decades of military authoritarianism. The 1957 coup that ousted Prime Minister Phibun Songkhram paved the way for Sarit Thanarat and Thanom Kittikachorn’s military regime, which consolidated power through the abolition of the constitution, dissolution of parliament, and bans on political parties. Sarit’s regime (1958–1963) justified its rule through anti-communism and economic modernization, relying heavily on U.S. aid and Vietnam War-related spending to fuel growth.

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, Thailand’s economy had grown rapidly, but industrialization was skewed toward urban areas, and wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few conglomerates. This widened the gap between urban and rural areas, exacerbating poverty, landlessness, and corruption. Meanwhile, resentment toward U.S. military bases (which were seen as a source of social disruption) and the regime’s repression of political dissent created a tinderbox of discontent. The military’s use of martial law and censorship suppressed formal political participation, pushing opposition into universities and intellectual circles, where radical ideas began to take root.

III. Rise of Student Organizations and Political Mobilization

The National Student Center of Thailand (NSCT), founded in 1968, emerged as the core organizational platform for the 1973 movement. Initially focused on student affairs and community service, the NSCT did not directly challenge the military regime until the early 1970s. However, rising inflation, the expansion of Japanese and U.S. corporations (which fueled economic nationalism), and the regime’s crackdown on dissent pushed the NSCT toward more radical politics.

In 1972, the NSCT launched a successful boycott of Japanese goods, demonstrating its ability to mobilize support beyond campus. This success emboldened student leaders, who began to engage with socialist, anti-imperialist, and democratic theories. While the Thai Communist Party (TCP) did not formally ally with the NSCT, its discourse—including critiques of feudalism, imperialism, and dictatorship—influenced many students, spreading ideas of "democracy," "social justice," and "anti-imperialism" across campuses.

The trigger for the 1973 uprising was the June 1973 expulsion of nine Ramkhamhaeng University students for criticizing Thanom and Deputy Prime Minister Praphas Charusathien’s extension of military service. The NSCT organized a sit-in at the Democracy Monument, demanding the restoration of the constitution and an end to military rule. This marked a shift from campus-focused activism to direct confrontation with the regime.

IV. Outbreak of the Movement: From Petition to Street Confrontation

In early October 1973, 13 scholars and students were arrested for distributing leaflets demanding a new constitution, sparking days of protests. Demonstrators called for the release of the detainees and urged the government to commit to a timeline for constitutional reform. The military regime viewed this as a direct challenge to its authority.

On October 13, tens of thousands of protesters marched from Thammasat University to the Democracy Monument, surrounding Bangkok’s political center. The following day (October 14), security forces opened fire on crowds near government buildings and major intersections, using tanks and helicopters to suppress the protests. Dozens to over seventy people were killed, and hundreds to thousands injured (casualty figures vary by source).

The bloody crackdown further inflamed public anger, leading to clashes between protesters and troops across the city. The situation teetered on the brink of full-scale violence, forcing the monarchy to intervene.

V. Role of the Monarchy and Military: Limited Support and Compromise

King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) and the royal family played a pivotal role in resolving the crisis. In the official narrative, the King intervened to stop the bloodshed, compelling Thanom and Praphas to resign and go into exile. He then appointed Supreme Court Chief Justice Sanya Dharmasakti to lead a civilian interim government, which promised to draft a new constitution and hold elections.

This arrangement satisfied the protesters’ core demand—ending direct military rule—while preserving the military’s structural influence in politics. It also avoided a revolutionary collapse of the regime, maintaining stability. From a political sociology perspective, the monarchy’s mediation reflected the delicate balance of power in Thailand’s political system: the King, by "siding with the people" at a critical moment, restored some of the moral authority eroded by the military’s autocracy and channeled the movement’s radical potential into a manageable constitutional framework.

However, the 1976 Thammasat University massacre (where right-wing forces killed dozens of student protesters) revealed the limits of this compromise: the military’s structural dominance remained intact, and no stable democratic system was established.

VI. Relationship with the Left and Thai Communist Party: Alignment and Tension

The 1973 student movement is often linked to the Thai Communist Party (TCP). On one hand, scholars note that the TCP’s discourse—including anti-imperialism, anti-military dictatorship, and land reform—had a demonstration effect on student politicization since the 1960s. Many radical students were exposed to the experiences of China, Vietnam, and Cuba, which shaped their views on revolution.

On the other hand, the NSCT and other movement organizations deliberately avoided being labeled "pro-communist" to attract support from the urban middle class and moderate opposition. Their public demands focused on "democracy," "constitutional rule," and "anti-corruption," steering clear of explicit leftist slogans.

This "left-leaning values, strategic distance" approach had complex consequences. In the short term, it gave the movement broad social legitimacy. However, when the military and right-wing forces cracked down on Thammasat students in 1976 (using "anti-communism" as a pretext), many students had no choice but to join the TCP’s armed wing. This post-hoc alignment was then used by right-wing narratives to frame the 1973 movement as a "communist conspiracy."

VII. Conclusion: Democratic Myth and Capital Resurgence

The 1973 student movement succeeded in breaking the military’s "untouchable" myth and opening a crack in the edifice of Cold War authoritarianism. However, this crack was quickly sealed by the discourse of "universal democratic values," which reframed the movement’s radical potential into a form compatible with capitalism.

While the movement toppled Thanom’s regime, it also provided the system with an opportunity to renew itself: the military retreated to the background, and a civilian government (elected through "democratic" means) restored legitimacy. This allowed the urban middle class to feel that Thailand was "modernizing" and "normalizing," while reassuring Western powers that Thailand was on an "acceptable democratic path"—ensuring continued capital inflows and aid.

The 1974 constitution enshrined provisions on human rights, press freedom, and political parties, leading to a brief opening of media and public space. However, this was more of a "system detox" than genuine reform: it added a layer of "freedom and rights" to the existing order without touching the structures of conglomerates, land relations, or transnational capital. The proliferation of new political parties and civil society organizations expanded formal channels for participation but domesticated radical class politics and anti-imperialist critiques into a "manageable civil society" spectacle.

The movement expanded the boundaries of the political community, bringing the demands of workers, farmers, and urban poor into the public agenda. Issues like wealth inequality and regional disparity were discussed, but framed in technocratic terms ("uneven development," "good governance") rather than as structural exploitation or dependent capitalism. The urban, university-centric nature of the movement meant that rural and marginal areas were treated as background rather than political subjects.

Ideologically, the movement remained stuck between liberalism and moderate leftism: it borrowed the universal language of "democracy" and "human rights" but failed to develop a systematic critique of the "state-capital-military-monarchy" power bloc. When the military and conservative alliance returned to power, the movement could only appeal to procedure and morality, lacking aalternative vision to mobilize the masses.

The monarchy’s role as "final arbiter" in the crisis seemed to side with the people, but it effectively positioned itself as a moral center above politics. By ousting the military regime, it restored its symbolic authority (eroded by decades of military rule) but locked all radical possibilities into a framework of "monarchy-military-middle class" order. This left the door open for the military to use "defend the nation and the King" as a pretext for future interventions, providing endless legitimacy ammunition.

References

1. Benedict Anderson (班纳迪克·安德森): Withdrawal Symptoms: Social and Cultural Aspects of the October 6 Coup (1977).

2. Duncan McCargo: Network Monarchy and Legitimacy Crisis in Thailand (2005).

3. Pasuk Phongpaichit & Chris Baker: A History of Thailand (2005) 及 Thailand's Boom and Bust.

4. Seksan Prasertkul (色讪·巴色军): The Transformation of Thai Society and Politics.